Archive

The Internet is a Basic Human Right, Even China Agrees.

In an effort to warn about the risks of misuse of networks as in China’s sovereign power to patrol the Internet, Jonathan Zittrain states: “Perhaps it is best to say that neither the governor nor the governed should be able to monopolize technological tricks.” (pg. 196, Future of..)

For example, the blocking and unblocking of Wikipedia in China without announcement or acknowledgment—might be grounded in a fear of the communal, critical process that Wikipedia represents. In the days leading up to Google’s decision last week to remove its Chinese search engine from China, there is much debate about the future of the generative Internet in that part of the world.

While the Internet exploded in popularity for Americans in the 90s amidst a blizzard of AOL discs and disconnects and dot-com booms and busts, it wasn’t until the last decade that it went mainstream for the Chinese. And, China has done quite well making up for lost time.

Google has been there since 2006 and realizes more than anyone that Chinese Internet users have become a defining element of modern Chinese society. In fact, there are now more Chinese online than there are Americans in this world. (China now has over 384 million Internet users, which is nearly 80 million more than the population of the United States.)

Google’s public complaint about Chinese cyber-attacks and censorship reflects a recognition that China’s status quo – at least when it comes to censorship, regulation and manipulation of the Internet – is unlikely to improve any time soon, and may in fact continue to get worse.

Chinese government attempts to control online speech began in the late 1990’s with a focus on the filtering or “blocking” of Internet content. Today, the government deploys an expanding repertoire of tactics. Zittrain calls them “technological tricks.”

Filtering is just one of many ways that the Chinese government limits and controls speech on the Internet. They have also engineered ways to delete content at the source, have developed domain name controls, ways to disconnect and ways to launch cyber-attacks.

China is pioneering a new kind of Internet-age authoritarianism. It is demonstrating how a non-democratic government can stay in power while simultaneously expanding domestic Internet and mobile phone use. In China today there is a lot more give-and-take between government and citizens than in the pre-Internet age, and this helps bolster the regime’s legitimacy with many Chinese Internet users who feel that they have a new channel for public discourse. On the other hand, reports state that the Communist Party control over the bureaucracy and courts has strengthened over the past decade, while the regime’s institutional commitments to protect the universal rights and freedoms of all its citizens have weakened.

But, there is great hope for the generative Internet and no one understands that better than the Finns, who last October made Finland the first country in the world to declare broadband Internet access as a “basic human right”.

With the revolution having thus begun by the Europeans, it is perhaps not surprising that four out of five respondents to a recent BBC World Service poll believe access to the Internet is a fundamental right. And these feelings are particularly strong in South Korea and China.

More notable findings from this study using 27,000 adults across 26 countries:

- 78% believed the Internet gave them “greater freedom”.

- And over half feel the Internet shouldn’t be regulated whatsoever by any governments anywhere.

- South Koreans, Mexicans, and Nigerians apparently felt most strongly about this.

- Whereas Pakistanis, Turks, and Chinese did not.

- Americans were ahead of the curve when it came to expressing opinions online.

- 65% of Japanese, however, felt differently, that they couldn’t “safely” express themselves on the Internet.

- People in France, Germany, South Korea, and China felt likewise.

- Over 70% of respondents in Japan, Mexico, and Russia said they couldn’t live without being able to go online.

- But respondents feared online fraud, more so than violent/explicit content and threats to their privacy.

- 9 out of 10 said the Internet was a good place to learn.

- Nearly 50% say that the Internet was valuable for finding information.

- Over 30% valued it as a means of communicating and interacting with others.

- But only 12% valued the Internet as a source of entertainment.

China is going to continue to be the focus of the expansion of the generative Internet. Hopefully, if companies like Google are patient enough they will be able to affect some changes in Internet filtering and over-cautious censorship. And free speech advocates want to see the Internet do what we were promised it would — connect people, serve as a check against abusive governments, and ultimately serve as a democratizing force throughout the world.

How To Save Our Weapons of Mouse Destruction!

Our recent debates about the need for new U.S. laws to protect our privacy on the Internet are all inspired by the very negative emotions of shame and disgust. Where’s the love? Some smart people in this debate contend that our system of law cannot be understood without some reference to the emotional impact on those people the law is meant to protect.

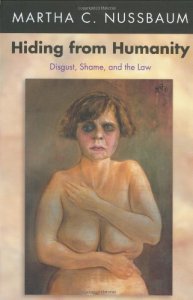

For instance, Daniel Solove invokes the help of the philosopher Martha Nussbaum to define ‘shame‘ in his book, The Future of Reputation. Her book Hiding from Humanity, I think, is even better as a philosophical treatise on the difference between norms and the law. Her greatest critique and the point that Solove avoids in his arguments is that we should be wary of laws that have as their sole agents the emotions of ‘disgust and shame‘ because indulging in those emotions allows us to hide from our humanity. She refers not only to our humanity in the general sense but also to those specific features of our humanity that are most animal-istic: our vulnerability and mortality.

Nussbaum portrays emotions and vulnerability as fundamentally intertwined, and interprets laws as defenses against human vulnerability to a wide variety of harms. However, Nussbaum takes the strong position that disgust is never constructive in law, and in those cases where it might seem to be useful, indignation is actually the more appropriate constructive emotion.

Can you imagine putting ‘disgust and shame‘ on a continuum for the courts to decide? The ruling would read:

“well, let’s see, this example is ‘mildly’ disgusting and embarrassing and deserves a “3”while this is other example is ‘really’ disgusting, so let’s give that one a ’10’!”

As Nussbaum contends,

“we cannot trust disgust to carry innate wisdom or any meaningful correlation to what is really harmful and …, disgust prompts turning away from a stimulus or issue rather than constructively handling it.”

Discrimination of Jewish people and subordination of women are the result of laws based on disgust. Most people respond to disgust by distancing themselves from the object. In Nussbaum’s view, this “out of sight, out of mind” reflex undermines the ability to productively use disgust in fighting for progressive causes such as human rights.

For example, disgusting images from the genocide in Rwanda motivate some to turn away from the information and avoid learning more about it, which in turn prevents them from actively working to prevent future crimes against humanity. For others, the images are seared into the memory, and they are thereby motivated to support the prevention of such crimes. Their indignation supersedes their disgust. This type of ‘positive’ rage against the breach of human rights embodies the best kind of wisdom that has spawned the most meaningful and productive laws like anti-discrimination, for example.

Solove needs to take heart as he admits the dilemma in trying to embolden laws based on general themes of disgust, shame, guilt, depression, embarrassment, humiliation and rage. The digital socialism reinforced by the ‘open source’ world of the Internet not only exposes all of us to unprecedented sharing of our formerly ‘secret’ inner lives but also challenges us to come to realize our most difficult ability – the group consensus.

In fact, it is empirically proven in studies that the decisiveness of other cultures differs considerably from that of Americans. The Japanese, for instance, have assimilated values that actually promote building a group consensus at the expense of individual initiatives. My personal favorite is that the universal use of wearing a gauze mask in Japan to prevent others from catching the mask wearer’s cold is easily seen in America to be an embarrassing few who wear masks to prevent catching a cold from others! In Japan, it’s all about what’s good for others, in America it’s all about what’s good for me.

American culture clearly emphasizes individual decision making through concepts such as freedom and rights. We like being anonymous and selfish and singularly righteous about, well…just about anything. We also don’t care much for laws that inhibit our ability to ratchet up our personal weaponry or our scopes or our recorders.

Fortunately, our founding fathers were able, after much debate, to actually reach a group consensus and free up our speech and our press and protect our privacy as best they could. They decided to defer on the topics of gossip and rumor and the Internet.

So, instead of passing new laws because we are so disgusted or shamed about our reputations and secrets we should instead gather up our indignation and rage and channel it to admit that the Internet is the world’s free and open source binoculars, microscopes and recorders and weapons of mouse destruction. And so, let’s just be downright indignant and determined to muster up some tough laws that make sure we teach that wide-open-source lesson to the next generation!